Hexahexes

Copied and pasted directly from the blog post of the same name!

Introduction

I always sort of overlooked polyhexes in the past. Polyominoes were the main event, so to speak, and the first polyforms I really got properly into, and on the rare days I wanted a really infuriating challenge I would usually turn to the polyiamonds. But polyhexes for whatever reason just weren't really on my radar. Sure, I had a physical set of the 1- through 5-hexes from Kadon, and I solved a couple of things with them. And I even made a half-arsed blog post a while back. But that was about it really. Until now.

A few weeks ago on a whim I got a set of hexahexes cut out of the cheapest MDF money could buy. I didn't even shell out the extra two quid for the laser cutting people to cover the wood with protective masking tape, instead opting to let the bits get gently toasted around the edges by the laser. And then I took them on holiday, to a chilly weekend in a caravan in Northumberland where I knew I'd be a captive audience in the evenings. And while there I slowly began to realise that I'd missed out... Polyhexes were fun. In fact they weren't just fun, but were in fact... very fun.

This photo doesn't really give any sense of scale, but each hexagon is 8mm to an edge, and the full solution has a diameter of about 40cm or so on average. I think. Nice and chunky. I actually checked the scale this time before cutting unlike my positively tiny enneiamonds.

The slight browning of the edges turned out to be something of a blessing in disguise - it makes the borders between adjacent 'hexes stand out a bit in photos which is handy. Sometimes I'm too lazy to draw up a pen-and-paper record of a solution, so just being able to take an aerial photo that I can work from to create a digital image is a nice time-saver. And talking of digital images:

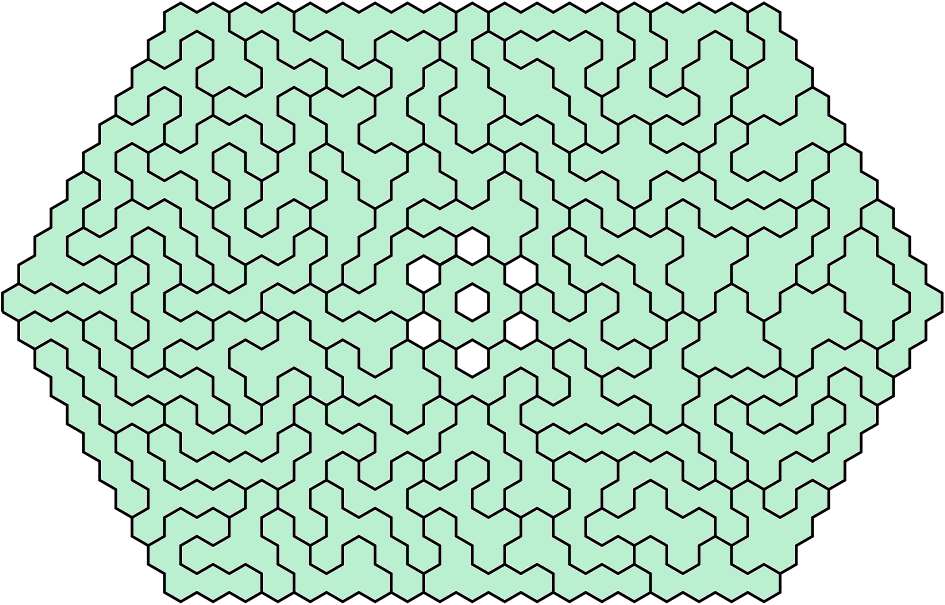

Here are solutions to two different hexagons, the more compact one is the shape of the solution Kadon uses for Hexnut II; the larger thinner hexagon I haven't seen anywhere before. I haven't ran the numbers for hexagons larger than this; it could be that there is an even bigger thinner (and therefore harder to solve) hexagon ring out there waiting to be found.

Speaking of, solve difficulty is the best thing about the hexahexes. It's somewhere between that of hexominoes and heptominoes, I'd say. A good, meaty challenge but one that I don't need to set aside a whole evening for. There are a couple of kinks to be ironed out with my solving technique, though, mostly the fact I'm not used to hexagons so it's often not immediately obvious whether a piece will fit in a certain place without actually trying it a few different ways.

Un-holey Hexahexes

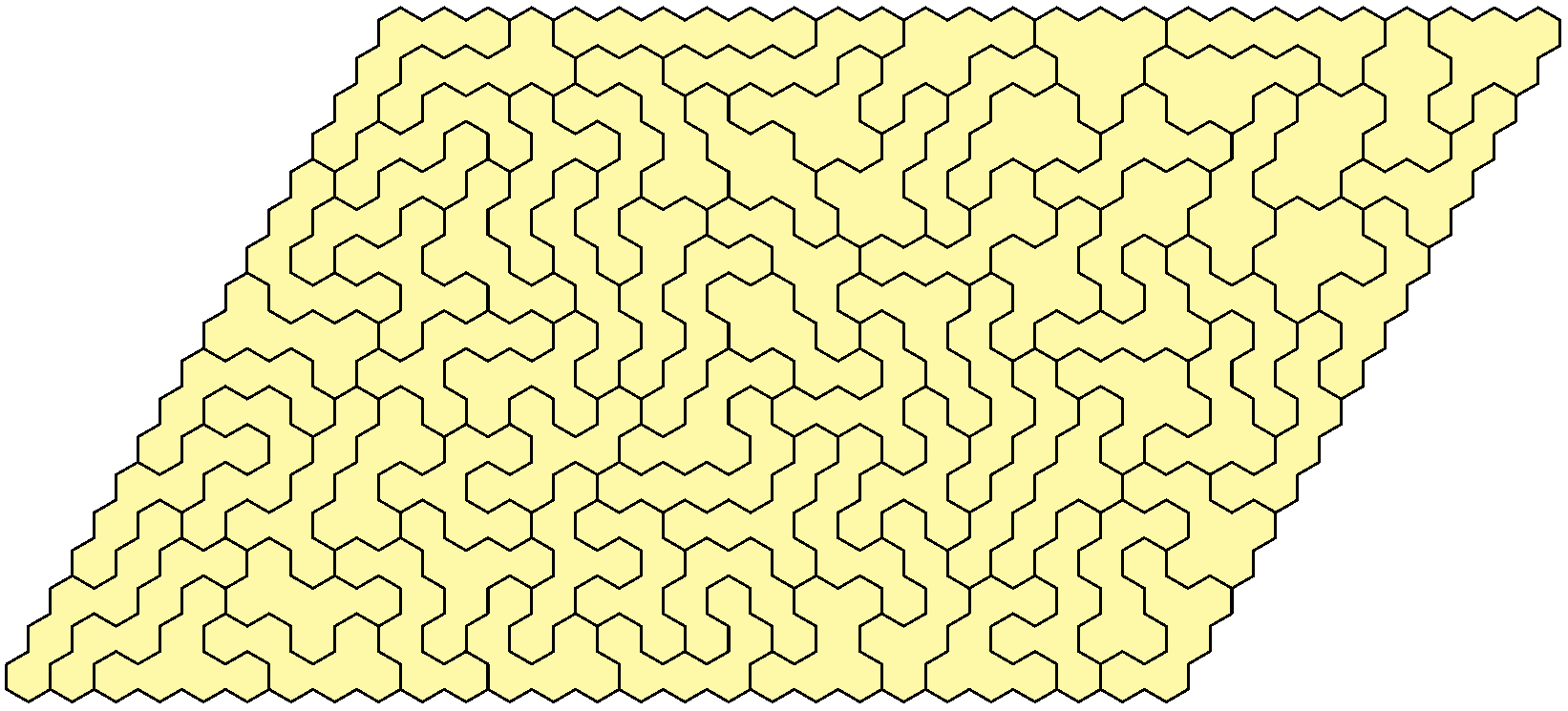

If you discard the holey hexahex (as we sort of unintentionally did for the rings above) you get 81 pieces and a total area of 486 hexagons, which divides up very nicely indeed. So far all I've done with this set is the really easy stuff - a couple of approximations of parallelograms, of which one is shown below for your perusal.

The 81 unholey hexahexes squeezed into an 18x21 parallelogram. Solve time approx. 45 minutes manually.

But there's a lot more out there than just parallelograms. It's fairly easy to work out formulae tying the edge lengths to the area for various hexagons, triangles and other such shapes that hexagons lend themselves well to. And from there just a little bit of searching for edge lengths that give the magic number, 486.

Finding shapes to make

This isn't touched on nearly enough on other sites. The process of finding which shapes are possible to construct with a given set of pieces. Sure, with squares or parallelograms it's easy enough - just factorise all the numbers from the total area of the pieces upwards and hope there's one that breaks nicely into two large enough side lengths to work with. And hope that the number of holes lets you do something nice with them too. Nothing worse than realising your potential even x even rectangle needs an odd number of holes, guaranteeing at least one of them will be hideously off-center.

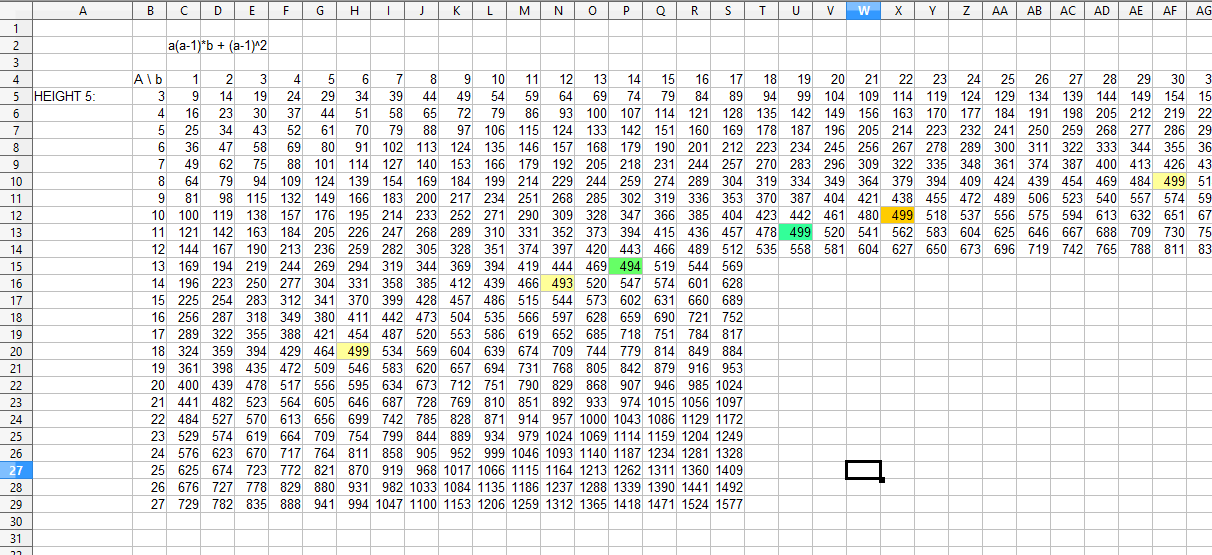

But when it comes to more adventurous shapes, you need to get a little bit creative. Generally, I try to find a formula that gives the total area when fed in the values for however many edge lengths. In the case of hexahexes, for example, a hexagon with two lines of symmetry should be workable, and the formula A = ab(a-1) + (a-1)² gives the total area for a hexagon with a unit hexagons in its shorter diagonal and b unit hexagons in the longer diagonal.

Determining these formulae is an art unto itself. The usual approach is to break your shape up into squares or rectangles (in the case of polyominoes), or parallelograms and triangles (in the case of polyhexes), then get expressions for the areas of those separate bits individually. All of this goes to hell when you try it on polyiamonds though.

Once I've got the formula it's then a case of making a big, ugly and confusing-to-the-untraind-eye Excel spreadsheet (actually, it's an OpenOffice spreadsheet because I'm cheap) where every possible combination of values for a and b are evaluated. Then it's just a case of going through and finding the values that are equal to or slightly greater than the total area you want. For hexahexes it's 492 (6x82), and all the likely candidates will fall on roughly a nice curve like in the picture below.

Click the image for bigger (if you're into dull spreadsheets)

Then after this step it's easy. Take a punt at sketching out the shape with a configuration of holes that looks half way presentable, then dig out the hexahexes and clear a flat surface and get some solving done. Admittedly, feeding the shape and the pieces into some solver software will yield much the same results in a fraction of the time, but where's the fun in that?

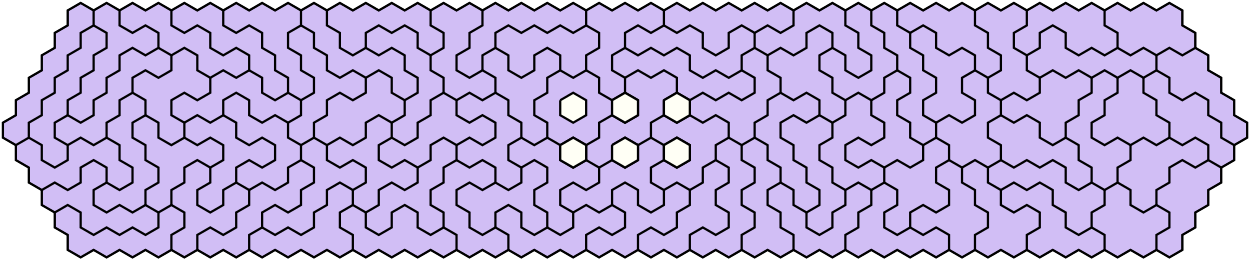

And here's a width 11 one, just for the hell of it. A website-only exclusive because I can't be arsed to edit the blog as well. Too much effort.

Previous: Pentahexes | Next section: Hexahexes, Part 2

[ Home > Polyhexes > Hexahexes ]

Lewis Patterson. Last updated 07/02/24.